A mighty fortress is our God. That is the most famous of all Lutheran hymns, by far – a symbol of our church and of its heritage. We sing it in worship, Mendelssohn made it the basis of his Reformation symphony, some of us grew up hearing it on the Davy and Goliath cartoon show. It is based, loosely, on the 46th Psalm, which says that “God is our refuge and strength,” that the “Lord of hosts is with us and the God of Jacob is our stronghold.”

There is a story, we can’t be sure it’s true, that the song played a crucial role in the history of the church. In the year 1530, Europe was in crisis over matters of religion and the emperor wanted nothing more than to crush all dissent and rule a united church. So he called a meeting of all the German princes, in the city of Augsburg, inviting them to present their beliefs so that he could pick and choose. And if anybody disagreed, too bad, he was the Emperor, he had the biggest army.

Luther could not be there himself; he was an outlaw, and could be taken captive. But his friend Philip Melanchthon wrote up an essay – a confession of faith, a sort of creed – describing the Gospel as the evangelicals understood it. And then, according to the story, the Saxon princes – Luther’s princes, and the other lay people who supported the Evangelical movement, what today we call the Lutheran movement – they marched together into the city, carrying this confession of their faith and singing this song together.[1]

They were not afraid of the Emperor, or of his soldiers, or of his wrath, because they trusted in somebody far greater and more powerful. The God of Jacob, they sang, is our stronghold; our God is a mighty fortress.

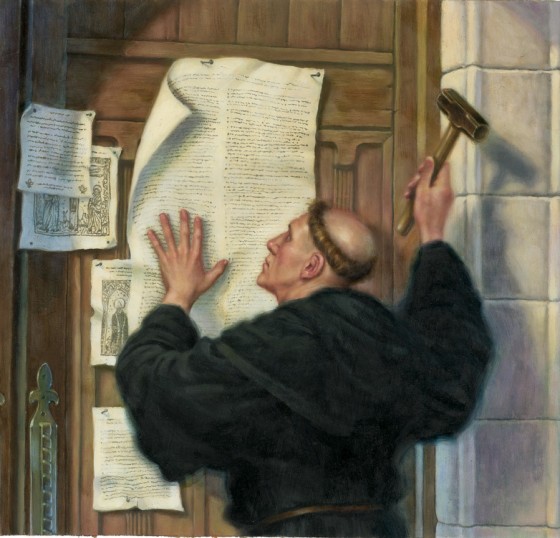

Some people say that the posting of the 95 Theses, which we remember today, was the birthday of the Lutheran Church. But that was just one scholar inviting other scholars to an academic debate. I think it was Augsburg in 1530 – the Confession of Faith, the lay leaders chanting Luther’s anthem, the Evangelical Movement claiming its faith despite all opposition – I think this was the real birthday of the Lutheran Church.

Which begs the question of what, exactly, the Lutheran Church really is; of what it stands for. After all, we call ourselves Evangelicals, but we don’t look or sound like some of the churches that also claim that title. We call ourselves Catholics, too, but Pastor Terri is living proof that we don’t mean it in the Roman sense.. So what are we, who are, what do we stand for?

Well, the official answer is probably in the Confession of Augsburg – you can find it on your bulletin covers, in pale print. It says:

Human beings cannot be justified (that is, forgiven and made righteous) before God by their own strength, merits, or works, but are justified by grace, through faith, for Christ’s sake, when they believe that they are received into favor, and that their sins are forgiven for Christ’s sake, who, by His death, has made satisfaction for our sins. (Romans 3 & 4. )

That’s the dogmatic answer, but I’m not sure it’s very helpful. If somebody on an elevator asked me what it meant to be a “Lutheran,” I would not rattle off Augustana IV for them. I would tell them a story – and ironically, one that did not take place in a Lutheran church at all.

As a student, Terri worked for a while in a Baptist church in New Jersey. It was a friendly little place, with a strong social conscience and a good Sunday School – a lot like Our Saviour, I guess. And there was one little boy who came to Sunday School, a boy named Larry – he walked there from home, his parents weren’t involved, didn’t bring him, but he walked there every weekend because he wanted to hear the Good News about God and God’s salvation. But then one week Larry wasn’t talking, he wasn’t smiling, he wasn’t happy. So his Sunday School teacher took him off to the side and asked him what was wrong. He didn’t want to answer, but he started crying. He was quivering, shaking, clearly terrified. The teacher began to wonder if everything was okay at home, if he had been hurt or threatened. But then, at last, he looked up at her with tears in his eyes, literally quivering with fear, and he asked, “Is Larry written in the Lamb’s Book of Life?” (Cf. Rev. 21:7)

He was worried about his own salvation. He was a little boy – seven or eight maybe? – and he came to church to hear how much God loved him, but somewhere along the line he had been told that maybe he wasn’t good enough for God to love, that maybe his sins were too terrible, or maybe it was just bad luck because at the beginning of time God simply hadn’t chosen him. And that as a result he was damned, condemned, doomed to everlasting death and fire and worms never turning. He was terrified, and his church could not offer him any comfort; it was his church that had terrified him.

He was not the victim of domestic abuse. He was the victim of ecclesiastical abuse.

And that is why you and I are here today. Because five centuries ago a young priest named Martin trembled with that same fear of death and hell, that same fear that he was not good enough or pure enough; trembled until he looked deeply into the Scriptures, and saw that Jesus was not his accuser but his savior, saw that the God of Jacob was not his prison but his stronghold. Saw that he was saved not by his own merit, but by God’s gift.

And we are here because even now, five centuries later, much of the Christian world does not get it. Even among Protestants – these days especially among Protestants – the Scriptures are used as bludgeon rather than a balm, people are scared into believing with the threat of hell, rather than romanced with the promise of heaven. And they are made to believe that salvation somehow depends upon themselves – their good works, their prayers, their belief – rather than upon Jesus and his Cross.

So we are here, we few, we sixty or seventy million among the world’s billions, we Evangelicals in the old sense of the world, we for whom the Gospel is a promise not a threat. We are here, as we have been here five hundred years and as God willing we shall be here until the Lord returns, we are here to tell the world that salvation is not earned but given, paid for not by our strength, merit or works but by the Saviour’s blood. We are here to say that to the world, and to say to the God who loves us so much, Thank you; thank you, God, for the grace that you have given us through Jesus Christ, our Lord. Amen.

[1] Per D’Aubigne, Hist of Ref. (1843). John Julian finds 1529 and Speyer more credible, but w/o evidence.